Binary Space Partitioning (BSP)

littlebunny06

littlebunny06’s Ramblings on BSP: The Undiscovered Country

Around the start of the COVID-19 pandemic, certain spheres of technical discussion materialized, and with this, technical developments. The Ray Madness studio appeared to curate raycasting projects. Many creators started creating. Around this time in 2020, a few brief and speculative mentions of this algorithm, BSP, appeared. I first saw mention of it from CubeyTheCube(Raihan142857). From there, I stumbled into Vadik1’s “perfect sorting” 3D engine. It had the ability to accurately sort intersections. It used BSP.

How Vadik1’s Algorithm Worked

Per every frame in the project, a custom block is called to operate on a list containing indices to each polygon in the scene. By selecting the first polygon on the list, it categorizes the other polygons into two groups: on the same side of the player(in front of the selected polygon), and on the opposite(behind).

These groups are formed within the original list(in-place), with same-side-to-camera polygons placed on one side of the selected polygon index in the list, and opposite polygons to the other. The start and end indices for these groups on the list are stored, and recursively passed into the custom block again, allowing the same process to occur on the sub-groups. This recursion terminates whenever a group has only one item left.

If you, the reader, have ever worked with comparison sorts, you may notice that this algorithm is some sort of partition-exchange sort(quicksort). It does indeed work quite like quicksort.

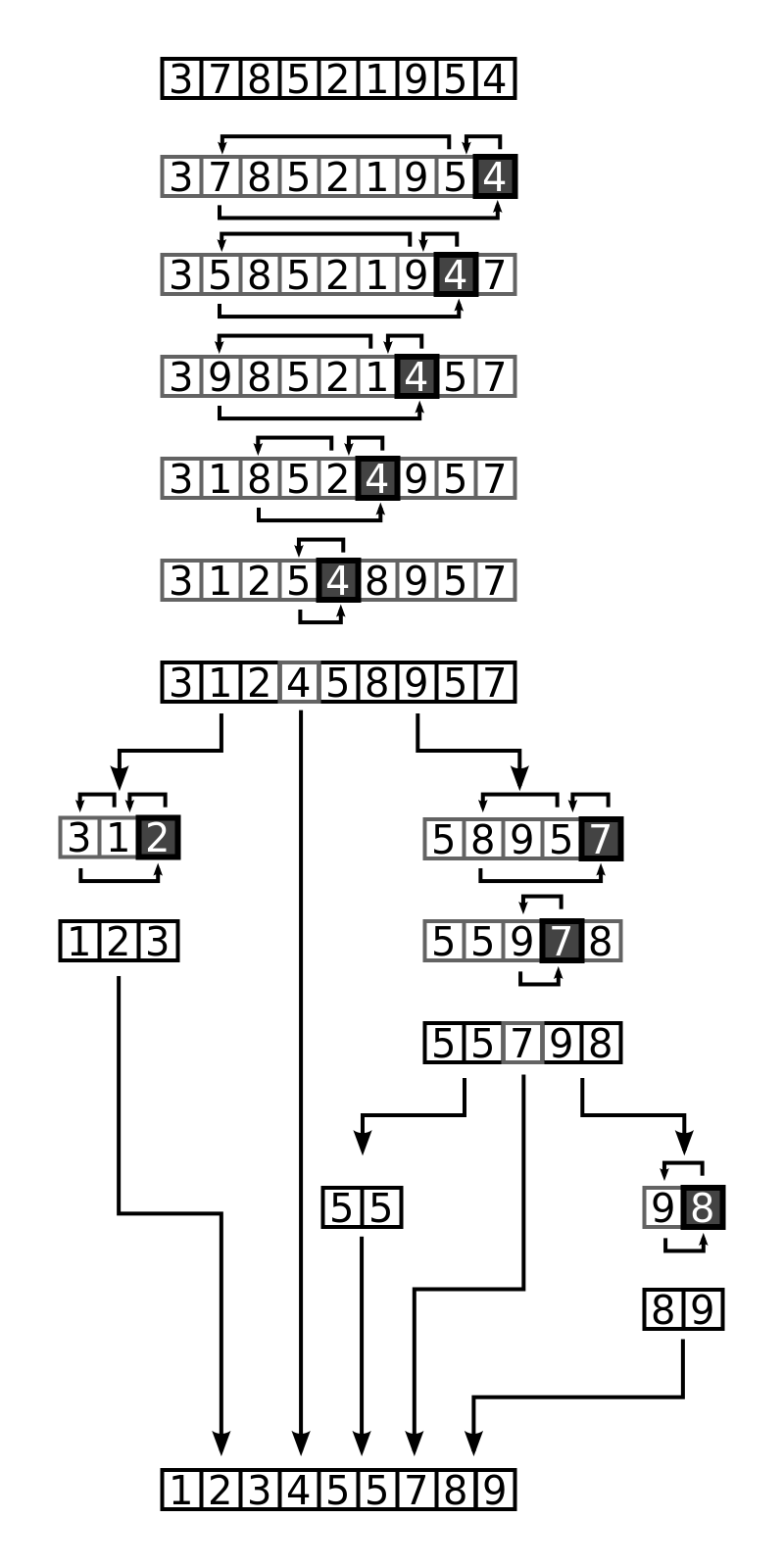

Here are the steps for an in-place quicksort algorithm:

- If the range has only one element left, stop the sub-routine(custom block)

- Otherwise, pick a value from within the range. This will be used as the pivot for the partitioning step.

- Partition by swapping the elements in a way so that all elements with values less than the pivot go before it, while elements with values bigger than the pivot come after it. Elements with values that are equal to the pivot can go either way. These swaps occur all-the-while keeping the pivot element’s position, which might move around during this step.

- Recurse the algorithm from the beginning of the sub-range up to the point before that of the division. Apply it to the sub-range after the point of division as well.

(From Wikipedia) Example of the Quicksort Algorithm on a random set of Numbers

So, Vadik1’s sorting algorithm works quite like a quicksort, only that instead of comparing values, the side which a polygon lands relative to a pivot polygon determines which group it falls into.

One thing which has been left out of this explanation, and that the reader may have noticed by now, is that some polygons are on both sides of a pivot. Vadik1’s algorithm deals with this by creating two new split versions of such polygons. These split versions are added to a separate, temporary list of polygons. This list is deleted upon each frame.

This algorithm produces a perfectly ordered list of polygons that can be rendered back-to-front in order to produce a perfectly sorted scene, even in the case of polygon intersection.

The code to this project, as well as Vadik1’s own description of how it works, can be found in this Scratch link: https://scratch.mit.edu/projects/277701036/

More Ramblings on BSP: The Traversal Into Rough Country

BSP Had Reached Its Limits

BSP was still an undiscovered country among the Scratch enthusiasts of 3D. As I dabbled into Vadik1’s code to produce my own 3D engine built on this concept, I had no idea what I was truly going to get myself into. Very soon, I entered a rabbit hole of graphics effects based on the idea first presented by Vadik1. I made the second iteration of Gamma Engine. It featured accurate polygon ordering with intersection support, and soon later, various graphics effects that relied on clipping volumes by using partitioning. By then, a couple more Scratchers were starting to pick up on the idea of BSP.

One of the big issues with this algorithm is that it’s slow. It's time-consuming to partition all the polygons and it stacks up as there are more numbers of them. Another issue is that, especially without any optimizing functions to help reduce split surfaces, certain scenes can cause a large buildup of split polygons after partitioning.

As I genuinely thought the limits of BSP had been reached, a Scratcher—Chrome_Cat—sought to solve these issues. After reading literature on the canonical implementation of BSP, he found his answer.

Then, There Were BSP Trees

A tree can be used to store the pivot polygons in each node. Upon each partitioning step, a new node is added to build this tree. The end result is a BSP tree, which can be traversed in linear time, in respect to the camera position, to access each node in correct render order. Chrome_Cat presented an algorithm that does such, and with the assertion that BSP trees could make the fastest 3D engine. It generated a tree in a compilation step, then traversed it on each frame during runtime. His 3D engine was indeed quite fast. It scaled up well. Within the generation function was a greedy pivot selection algorithm which looked through the range of polygons for one that would generate the least amount of splits. This allowed for massively reduced split counts on models.

Just as many of the fastest of all 3D engines of Scratch did not seem to have any significant room for optimization, this new idea was a breakthrough which, if not challenged the idea that 3D engines couldn’t be much faster technique-wise, brought new advances to a seemingly stagnating field. This however was the step into, what was at that point, the rough country of BSP as a technique.

I was also working on a 3D engine of my own alongside Chrome_Cat’s. This engine—the third iteration of Gamma Engine—also featured BSP trees. As I got further into the development of this Gamma Engine iteration, I would slowly find out that what I thought was all there was from the concept of BSP, was totally completely limited in actuality. But that will be a story for after we get a good idea of how a BSP tree is built and how it works on a conceptual level in Scratch.

Building A BSP Tree

Although the 3D implementations of BSP are 3D, of course, I will discuss 2D BSP trees for this explanation. This is because the principles of the 2D BSP tree which uses line segments extends to the 3D BSP tree which uses polygons.

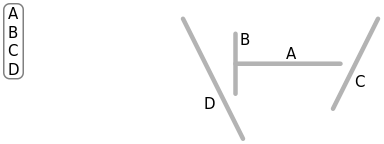

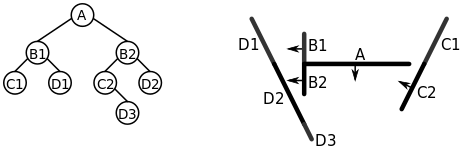

The below figure shows a set of four segments that constitute the scene. We want to split the world into two, and each part into two, and so on, in such a way so that each segment resides in its own unique subspace. There are unlimited ways to do this so the question is: How would we want to do this?

(From Wikipedia) A sample set of line segments in 2D space, and a list of the segments.

The simplest way is to simply split the world along the lines of the segments themselves. Each node would contain the wall that splits this scene. This is to be done recursively until a unique subspace boundary is created for each segment. This spatial organization provides an unambiguous visibility ordering explained earlier with Vadik1’s algorithm. This can be seen further as we get to the traversal step later.

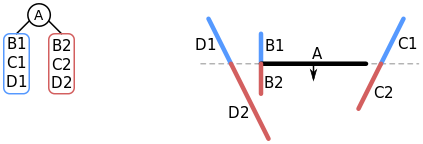

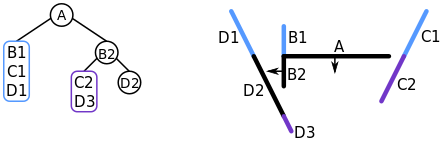

The first step in this process takes the splitting line from segment A, and groups the world into two parts, walls that are in front, and walls that are behind, just like what was explained with Vadik1’s algorithm.

A node is created, and segment A is added to the node. The actual implementation details will be explained in the Scratch implementation section next.

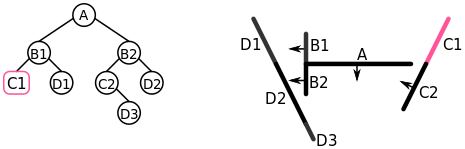

An issue with choosing A as the splitting line is that there aren’t actually any segments which are wholly in front or wholly behind A. So as you might remember, the solution is to break B, C, and D into B1, B2, C1, C2, D1, and D2 along the splitting line.

The remaining segments are grouped into the list of segments in front of A(B2, C2, D2), and those behind (B1, C1, D1).

(From Wikipedia) The initial split along the line of segment A.

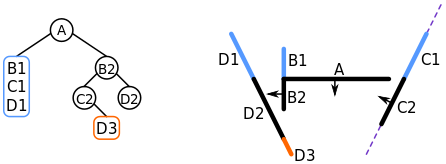

The algorithm is applied to the list of segments in front of A(B2, C2, D2). The front list is always processed first. Segment B2 is chosen and it is added to a new node. It splits D2 into both D2 and D3. Note that the new D2 is a split version of the old D2. D2 is added to the front list. C2 and D3 are added to the behind list.

(From Wikipedia) The split on the list of segments in front of A. B2 is chosen in this step.

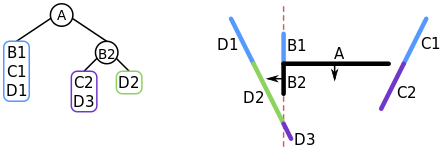

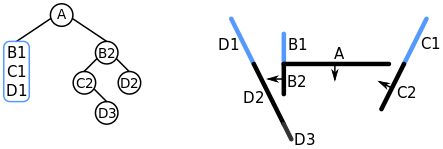

D2 is chosen and added to the node. Since it's the only one in its list, we stop there.

(From Wikipedia) D2 is chosen and added to a node in front of B2. It is the last item, so nothing further needs to be done.

As we are done with the lines in front of the node containing B2, we start looking at the list of segments behind it. C2 is chosen and added to a new node. The other segment, D3, is added to the list of lines in front of C2.

(From Wikipedia) C2 is chosen and added to a node behind B2.

D3 is added to a node. We stop here as it is the last segment in its list.

(From Wikipedia) D3 is chosen and added to a node in front of C2.

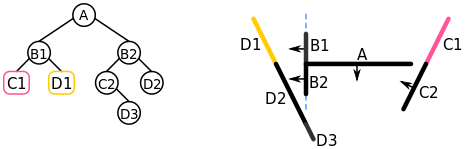

Since all of the segments in front of A have been added to their own respective nodes, we recurse on the list of segments behind A. We choose B1. It's added to a node and C1 is put into the behind list, D1 into the front list.

(From Wikipedia) B1 is added to a node, and C1 and D1 are grouped into their respective lists.

Finally, D1 is added to a node, then C1. The BSP tree is complete.

Now the BSP tree has been built, but it might not be immediately intuitive on how it helps with visibility ordering at all.